According to a new analysis by the International Rescue Committee, the US government’s tech-based immigration policies are preventing asylum-seekers from securely entering the country through US-Mexico ports of entry (IRC).

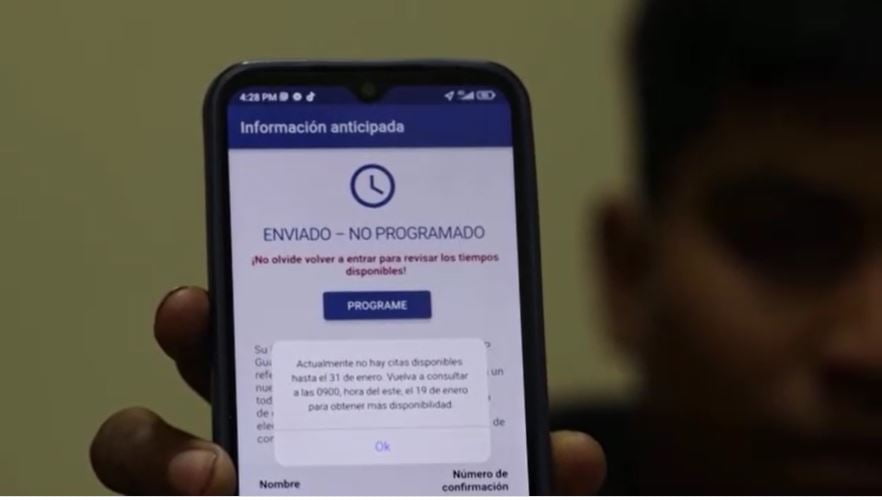

The International Rescue Committee’s working group of US, Mexican, and international NGOs discovered that new US regulations that prioritise the use of a Customs and Border Protection app to process border entries “renders most asylum-seekers ineligible for asylum, unless they use the CBP One smartphone app to schedule one of the limited number of appointments, or have sought and been denied asylum in a transit country with very few exceptions.”

The policy’s additional limited provisions worsen an increasing gap produced by the newly implemented digital track to asylum, as various human rights organisations noted early in the technology’s introduction.

“Holding access to seek and enjoy refuge on the ability of people fleeing for their life to book an appointment on a smartphone app is neither right nor realistic,” the paper concludes. “The CBP One app needs major upgrades, but even with those enhancements, it should never be the only way to request protection at a U.S. port of entry.”

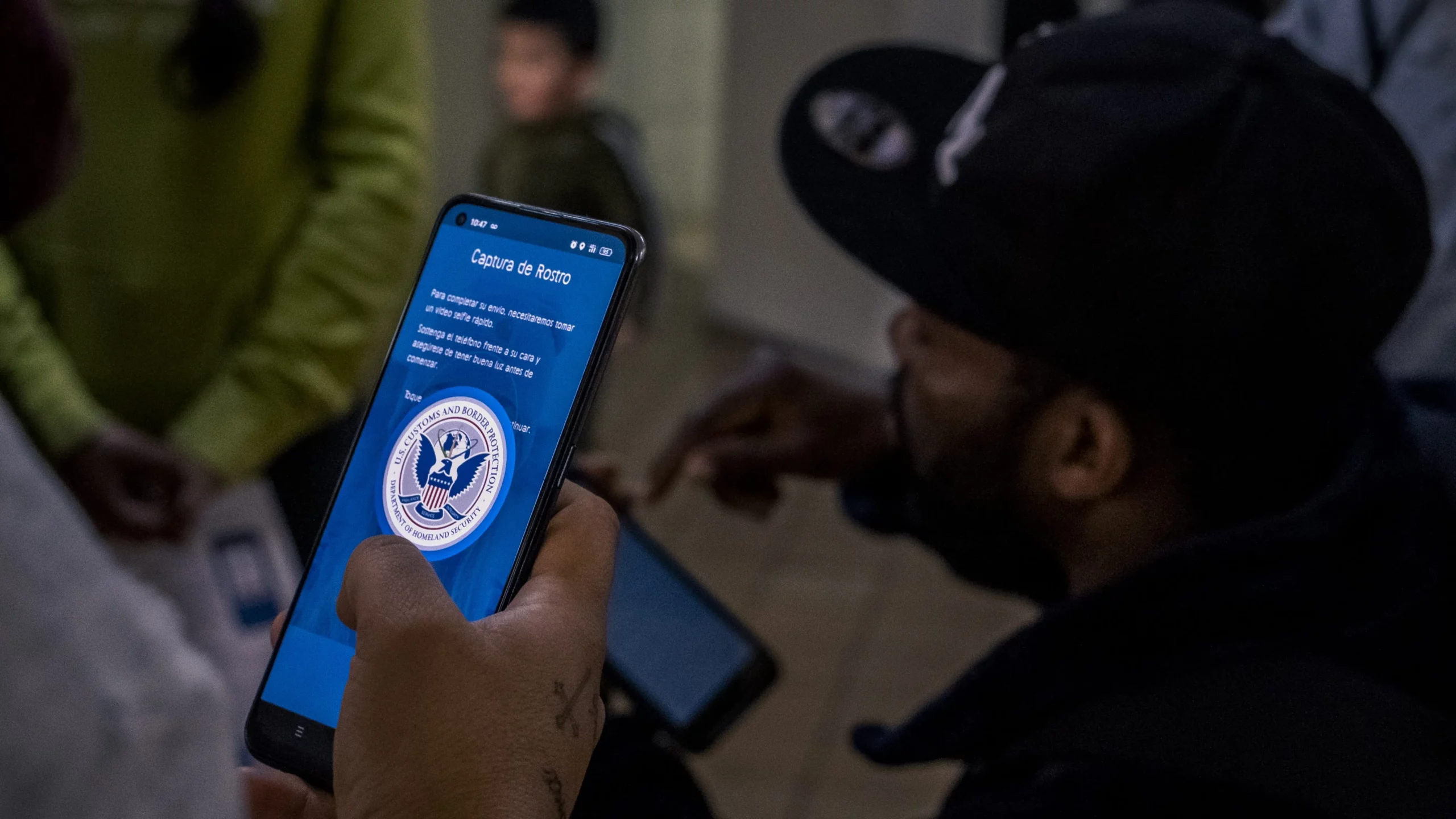

The CBP One app was first introduced in 2020 as an additional, though optional, portal for asylum applicants. It has, however, become one of the only avenues for migrants to access and confirm application requirements for claiming asylum in the United States. And, as of May 2023, it will be a requirement under President Joe Biden’s latest asylum policy.

There are only a few exceptions to utilising the CBP app to process applications, causing Amnesty International and other refugee advocates to accuse the US of violating its international human rights commitments by relying on the app. They’ve also noted a concerning lack of exemptions for “populations with circumstantial vulnerabilities, such as LGBTI people, families with small children, or others, such as Black, Brown, and Indigenous populations, who may face particular risk waiting in Mexico,” as well as a widespread lack of access to cellphones, stable Wi-Fi, and reliable information, which adds to the difficulties for migrants.

According to the IRC, between May 11 and June 12, 2023, only a small percentage of asylum requests were handled without prearranged meetings. Most typically, US and Mexican authorities barred asylum-seekers without CBP One appointments from physically entering the US to seek protection. While the frequency of app-based appointments increased in June, according to the organisation, government agents were still “metering” asylum seekers, resulting in long lineups, waitlists, and informal encampments outside ports of entry. The IRC and its partners also discovered that many people awaiting asylum had insufficient and inaccurate information about the new “asylum ban” regulation and the requirement for a CBP One appointment.

Activists have also raised concerns about digital privacy. In a May policy briefing, Amnesty International Americas Director Erika Guevara-Rosas stated, “The way the CBP One application works is very wrong.” “Asylum seekers are forced to install the app on their phones, which allows US Customs and Border Protection to collect data about their position by pinging their phones. The United States must ensure that asylum seekers enjoy due process rights in refugee status determination procedures and are not repatriated to countries where they may face harm.”

The most recent report, published in collaboration with Servicio Jesuita a Refugiados México, Refugee Health Alliance, Kino Border Initiative, Florence Immigrant and Refugee Rights Project, Espacio Migrante, and Immigrant Defenders Law Center, addresses many of these problems. The information was gathered at six U.S. ports of entry over the course of a month (May 11 to June 12), following the expiration of the country’s pandemic-era immigration regulation known as Title 42.

Title 42 of the Public Health Service Act of 1944 gives the government the authority to take emergency action to prevent the spread of contagious illnesses. During the early outbreak of COVID-19, President Donald Trump used it to restrict border crossings, halt asylum applications, and remove asylum-seekers who had already entered the United States. It was in operation under the Biden administration until May 11.

On May 11, President Joseph Biden’s new border plan went into effect, which still includes components of Title 42-era policy, such as the implementation of the CBP One app, a hyper-expedited deportation scheme, and a “third country transit restriction,” all of which have been highly criticised by advocates. Biden’s revised plan still requires asylum-seekers travelling through another nation to reach the US-Mexico border to first register a claim in the country they passed through, and those judged ineligible for asylum face a five-year prohibition from re-entering the US.

The working group recommends that the US government fully restore access to the asylum procedure, add agency staff (not military personnel) and other resources at ports of entry, and repeal the “asylum prohibition” to ensure “a safe, humane, and orderly process at ports of entry.”

To address typical information gaps between policymakers and asylum seekers, the IRC and humanitarian relief group Mercy Corps created the Signpost programme in 2015 to serve refugees’ and asylum seekers’ digital needs. Signpost now hosts three programmes that help migrants in Latin America: InfoDigna, InfoPa’lante, and CuéntaNos. Owing to increased demand, the IRC declared that it would extend InfoDigna services to ensure that more migrants had proper information before requesting for entry.